Classroom Layout Early Years#

It takes a special kind of person with a special kind of passion to be a teacher of young children. A teacher's effectiveness is directly correlated with their level of empathy and kindness. Teaching these kids will take a lot of time and patience.

Room arrangement, in my opinion, should be the first order of business. The learning environment a teacher creates for their students can either help them or hurt them. According to studies, it's important to foster an environment of trust and acceptance in the classroom so that students feel safe asking questions and sharing their ideas (Stronge, 2002). Children are highly attuned to their classroom environment. Is there a friendly and comfortable atmosphere in the classroom? Do all students have equal access to the classroom's resources? To what extent do the decorations brighten up the walls and make the students feel at ease, or are the walls bare and colorless? Is the function and layout of spaces clearly delineated? Scott, Leach, and Bucholz (2008).

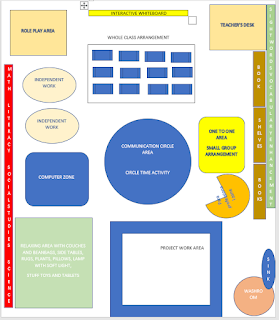

Please find attached a diagram/room layout of my classroom, which I have made as conducive to learning as possible. There are a total of 23 students in the class, according to the demographics. So that everyone in the class can sit with a friend, and because one of my students uses a wheelchair, I've arranged for them to sit in pairs.

Incorporating universal design principles into the classroom may ensure that there is enough floor space for pupils to walk about. The goal of universal design is to ensure that all goods and surroundings can be used by the widest possible audience with little if any, adaptation or special design (Burgstahler, 2008). I have divided the classroom into four sections: one for the teacher's desk, one for role-playing, one for quiet time, and one for the student's projects. To further aid pupils, the space has been outfitted with a number of different stations. I think educators should use the principle of universal design for learning to guarantee that all students have equal access to and use of all instructional resources.

Students will have the chance to unwind and play with the various props and furniture that have been placed in a designated "Role-Play" area. My desk is in one corner of the room, out of the way of students, and next to where I keep my papers. In one section, you may kick back on sofas and bean bags while perusing your iPad or reading a book from the stack of side tables. Warming up and softening up a classroom may be accomplished with the aid of plants, upholstered furniture, carpets, and cushions (Rutter, Maughan, Mortimore, & Ouston, 1979). The fourth section is designated as the project work area, providing a quiet and organized place for students to get their work done. In order to help my pupils, complete their assignments, I want to set up many small tables with seats and a variety of materials. The learning environment is designed to be both individual and small-group-based. In addition to ensuring students' safe access to the classroom, an ideal desk arrangement encourages students to become actively engaged in their education and to work together with their classmates. When having a class meeting or participating in circle time, it is customary to sit in a circle in the center of the room. Encouraging and supportive classrooms may be created when teachers instruct students in the art of problem-solving and conflict resolution via various group activities and whole-class discussions (Gartrell, 2006). According to Nelsen, Lott, and Glenn (1997), a class meeting takes place when the instructor sets aside time throughout the school day for students to gather in a group and address any concerns or difficulties that may arise.

Teachers may take preventative measures by establishing and sticking to a regular classroom schedule, which has been shown to have a favorable effect on students' academic performance and conduct (Cheney, 1989; Vallecorsa, de Bettencourt, & Zigmond, 2000). Active and quiet times, large and small groups, indoor and outdoor, child-directed and teacher-directed, visual cues, the use of a daily pictorial calendar, and active learning via hands-on experience should all be included in a classroom's daily routine. In addition to reducing the likelihood of interruptions, routines make it easier to switch gears between different tasks (Burden, 2003; Docking, 2002). To prepare kids for the morning meeting, they may be taught to put their belongings in a designated spot, praise their teachers, and sit in a circle upon their arrival. This is scheduled to take place daily for 15 minutes. The whole class will be divided into smaller groups to learn the new material. There will be 30 minutes allotted for this. After the topic is presented, students will be given the opportunity to work independently in a variety of settings, including small group sessions, individual task corners, and project areas. You have 90 minutes. Children will learn how to open, close, and otherwise manage food containers (such as milk and straws) on their own during snack time. They get a chance to practice and improve their social skills by interacting with their classmates. Give me 30 minutes. Children will learn to work together more effectively, solve problems creatively, think critically, and make sound decisions in a variety of small and big group contexts. This will take 2 hours. During "Choice Time," kids may do anything they choose, whether that's reading, coloring, watching TV, taking a sleep, or exploring the "Learning Zone." Each day, 90 minutes are set up for this. Therefore, a routine simplifies a complicated setting and informs pupils precisely what to anticipate, what is expected of them, and what is appropriate conduct (Burden, 2003; Cheney, 1989; Colvin & Lazar, 1995; Kosier, 1998; Newsom, 2001; Savage, 1999; Strain & Sainato, 1987; Vaughn, Bos, & Schumm, 2000).

All students, regardless of their ability level, are integrated into age-appropriate general education classes at their local schools, where they have access to high-quality instruction, interventions, and supports designed to help them succeed academically in the core curriculum through inclusive education (Bui, Quirk, Almazan, & Valenti, 2010; Alquraini & Gut, 2012). Successful inclusion occurs when educators recognize and value their students' unique strengths and requirements. Numerous research conducted over the last three decades have shown that inclusive education benefits students with and without impairments (Bui, et al., 2010; Dupuis, Barclay, Holms, Platt, Shaha, & Lewis, 2006; Newman, 2006; Alquraini & Gut, 2012). In the classroom, inclusion may be implemented in a variety of ways via carefully prepared activities. Lesson modifications and differentiation need a lot of time and effort to do well. It is true that adaptations, such as accommodations and modifications, play a crucial role in Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), but this is only the case if they are properly incorporated and implemented (Wilson, Kowalski, & IEP Complexities 4 Spencer, 2005). Students are pre-assessed on the topic you will be covering in class as a first step in the differentiation/inclusion process. Either a written exam or questions posed in class may serve this purpose. After you've administered tests and analyzed your students' results, you may begin looking for relevant activities and ideas to use during your next lesson. Differentiation is a powerful tool, and there are many resources accessible online to help us use it in the classroom. The curriculum can be taught in a variety of ways, including the use of brainstorming, buddy reading, buddy/peer support, the Bold Large Font size on graphic organizers, worksheets, reading the text, vocabulary, etc., group and pair work, video watch, experimentation, and, of course, teacher's supervision and support. It's challenging to choose the right methods to accommodate a wide range of pupils' requirements. Both the instructor and the student will experience frustration in the absence of proper preparation and the implementation of effective teaching methods.

Differentiation/inclusion will be supported via the use of many types of graphic organizers, as well as the teacher's presentation, experimentation, and video sessions. Supporting personnel, co-teachers, and specialist instructors will be required for small group or station instruction. When one instructor is focusing on a small group, the other teachers in the room may help the other kids.

The relationship between a teacher and a student can only grow stronger with open lines of communication between the two. An Individualized Education Plan (IEP) Meeting with parents is essential when dealing with children who have special needs because it allows teachers to better communicate with both parents and their kids. Parents must be consulted in order to gather information for a comprehensive report on the kid and to inform them of the resources and curricular adjustments that will be made to accommodate their needs. A monthly meeting is recommended.

After about two months into the school year, a joint communication with questions like "How has being in an inclusion classroom affected your child academically, socially, and behaviorally?" can be sent home. These questions come from the book Creating Inclusive Classrooms (Salend, 2001; referenced in Salend & Garrick-Duhaney, 2001). If there have been positive or negative effects on your kid, please explain them. Which factors triggered these shifts, if any? How has your child's enrollment in a mixed-age school impacted you as a parent? Both "What extra information on inclusion and your child's class would you want to have?" and "Please explain any positive or negative effects for you." It may be challenging for some parents to consistently participate in in-person sessions because of their work schedules. Using this method, they will be better able to share their thoughts and concerns with the school concerning their child's education.

Lessons for children with special needs might benefit from using a variety of approaches, including those that encourage student participation. Co-taught classrooms need more planning in order to ensure that students with special needs have access to the resources they need and that all students have a voice in the classroom (Walther-Thomas, Korinek, McLaughlin, & Williams, 2000).

Use strategies like as flexible grouping, activities that cater to different learning styles, student choice, and the creation of alternate activities and evaluations to differentiate teaching (Tomlinson, 2001). Students with exceptional disabilities benefit academically and socially from inclusion/differentiation strategies.

Students with and without disabilities learn more from a "general education" classroom when "Universal Design" principles are included in lesson preparation. According to the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework, "the core idea is that a curriculum should contain alternatives to make it accessible and acceptable for people with diverse backgrounds, learning styles, skills, and impairments in a broad variety of learning situations" (CAST, 2004, 3). Utilizing the whiteboard's interactive features, visual aids, and other multi-sensory techniques are all part of this. Allowing for a variety of student expression and participation in their learning (including writing, drawing, and speaking) (videos, software, and role-playing).

Giving students the chance to work on projects together or in pairs is another great way to help them improve their abilities. There are five considerations that should be made while these strategies are developed. Group work should be structured so that students depend on one another to complete a task successfully; (e) students should be held individually accountable; and (a) the task should be authentic, worthwhile, and appropriate for students working in groups; (b) small-group learning should be the goal; (c) cooperative behavior should be taught to and used by students; and (d) students should be held individually accountable (Putnam, 1998).

Students learn best when they are given a helping hand at the beginning of a new skill or concept and then allowed to go it alone after they have mastered it (Bender, 2002). The development of student autonomy as a learner is our primary focus. Students with special needs may be helped in a variety of ways; one such way is by breaking down large, difficult tasks into smaller, more doable ones. Students with learning disabilities can benefit from classroom centers by completing smaller tasks such as matching, filling in the blanks, and vocabulary flashcards; students with reading disabilities can be given large print books or flashcards; and students with learning disabilities can be given opportunities to write.

Teachers of students with special needs may best serve their students by using tactics including grouping, learning centers

, rotating lessons, selecting class themes, and making use of a varied collection of texts and resources.

Comments

Post a Comment